Disintegration of the Soul – Stasi Prison

This article may contain affiliate links where I make a small commission for purchases you make from links that you click from this article. By purchasing through these links, you support me at no additional cost to you. Thanks for your support.

Our short, spunky guide named Grit had us all circle around her in the cold, dimly lit prison cell. She started by asking us a simple question: “What is the first article of your country’s constitution?” The group was international, and one by one, each person tried their best to remember their country’s political backbone that they all probably learned as kids.

A man from Germany, a couple from Hungary, friends from Scandinavia, a solo traveler from the UK, and myself from the US all answered with some form of free speech and the right to choice. Grit then announced to us the first article about East Germany, run by the GDR, German Democratic Republic: “There is only one party.”

This set the tone for what we were going to see and experience for the next couple of hours. Imagine if you lived in a country where you couldn’t choose; you couldn’t express discontent with your government or even be associated with anyone who expressed discontent. This was East Germany and the GDR after World War II. It was a pawn in the cold war between Russia and America, and the people of East Germany were the losers. They lived in a world where they couldn’t speak up, were asked to share secrets, or were forced to make up lies about their neighbors and relatives, where they could trust no one – and the outcome of this society was the Stasi Prison.

The prison was opened by the East German Ministry of State Security, also known as the Stasi, in 1951 and was used until 1989, when East Germany was dissolved. At that time, it detained more than 16,000 prisoners who were considered actual and factual enemies of the government. This was not an actual prison – but more of a holding prison to get people to confess to ‘crimes’, and then they were charged officially and sent to a ‘real’ prison. However, this holding and interrogation prison time could last from 2 days to 2 years – blurring the definition of prison and interrogation as well as the concept of innocent until proven guilty.

Table of Contents

Two Prisons with Different Strategies

The prison had two ‘eras’ in a way – in the early 50s, it was run in the ‘traditional’ way, extracting confessions through torture and physical beatings, which took place in the Canteen cellar, also referred to as The Submarine. The basement prison was called The Submarine because it was dark, and, therefore, it was easy to lose track of time. Five to seven people were kept in a cell with a bucket for a toilet, and no one was allowed to talk or sit down. Grit showed us the various torture rooms and prison cells, making us all stand in the room together to try to imagine what it would be like in those days. I personally couldn’t even begin to imagine how people survived this.

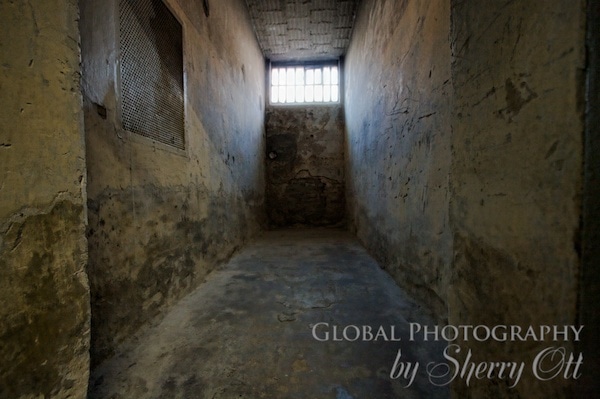

However, in the late 50s, the Stasi’s techniques changed immensely, and they built a new prison (by prison labor, of course), which was all about mental torture. Well-studied and implemented isolation techniques were put into practice – including sleep deprivation, total isolation, and threats to friends and family members. Much of what Grit told us and what I saw with my own eyes in the ‘new’ prison sounded more horrifying than the Chinese water torture room in the Submarine. This new section was all about mental torture that sent chills through my body.

Keep in mind that the people held here for unknown amounts of time were brought in sometimes on no evidence other than their neighbor or relative ‘ratting’ on them about something they said against the government. The Stasi regularly intimidated people and lied to them to get them to turn in their relatives or friends. People were so terrified (and rightfully so) of the Stasi that they would do anything to get off their radar. Basically, people who opposed the GDR’s policies were imprisoned and put through this psychological torture, referred to as the disintegration of the soul.

Inside the Walls

My footsteps echoed down the hall of the new section of the prison as Grit led us through each sterile section from the arrival garage, booking room, cell, solitary confinement, and interrogation rooms. The basement was where the isolation rooms were held – the walls were thick and padded in black, and absolutely no light was let in unless the prisoner were getting their daily food through a little slot in the door. The ground level was the arrival and booking rooms. The rooms were all tiled in a busy golden pattern, the doors were a drab blue/gray, and the halls seemed to glow yellow from the exposed fluorescent bulbs. The upper floors were precisely designed interrogation rooms, with every piece of furniture placed in its exact position for a reason.

As a prisoner, you never EVER saw another prisoner, even though there were 200 kept there at a time. A guard checked in on you every 3 to 5 minutes. This knowledge of the prison was really gained from first-hand accounts from former prisoners and guards as well as some documentation found in other German institutions; however, much of the documentation and any evidence of the operations were removed or destroyed after the fall of the wall. In fact, Grit told us a story of two men in the last decade who met in a bar and, after talking for a while, realized they were kept in prison at the same time.

Present Day

Today, the prison has been turned into a memorial referred to as Hohenschönhausen and is in the middle of a residential area, which feels out of place yet strangely normal in Berlin. You might think it is weird that this was my favorite site visited in Berlin, but the Cold War era was something I grew up in and was the most intrigued with among the myriad of depressing historical sites and memorials in Berlin. I actually enjoy learning about sites like these around the world – the Stasi Prison reminded me of similar tours in Cambodia of the S21 Museum or Robben Island in South Africa. The Stasi Prison was something that I absolutely knew nothing about, but you couldn’t help but feel the mental and physical anguish the prisoners lived with as you walked through the eerie halls. The tour itself was full of jaw-dropping information and you had ample time to look around the cells and rooms to get a real feel for the building and history.

As the tour wrapped up, one of the German tourists, the only American in our group, said to me, “I wonder if, in a few decades, people will be touring Guantanamo?”

More Information:

Currently it is only possible to view the Memorial Center as a guided tour (guides are volunteer former prisoners). There are public tours which do not require registration on weekdays at 11am, 1pm and 3pm; and at weekends hourly between 10am and 4pm . Admission is about €3 / €1.50 (concessions), and free on Mondays.

Hohenschönhausen Memorial Center (Stasi prison museum)

Genslerstraße 66

13055 Berlin

Germany

Tel.: (030) 986 082-30

Fax: (039) 986 082-34

Disclosure: Thanks to Oh Berlin apartment rental and Go with Oh for hosting me on this great tour. However, all of the opinions expressed here are my own – as you know how I love to speak my mind!

Interesting. Sherry, I’m in the middle of planning a week in Berlin with my spouse and kids. We’re naturally going to experience the standard fare — Brandenburg Gate, the Wall, new architecture etc. We don’t want to spend every day immersed in Berlin’s 20th century history but aren’t ignoring it, either. Would you say that the Stasi Prison is too depressing for a 10year old and young teen?

Hi Jennifer – I have thought a lot about your question – and I think the teen may enjoy it – but a 10 year old maybe not. It’s pretty heavy stuff and if they aren’t aware of the cold war and GDR it might be really confusing…not that they can’t learn! 🙂 However – it is pretty heavy – lots of talking by the guide and then you can wander the cells. The new prison cells are pretty normal – but the stories of the psychological stuff is not. However – I would recommend the Reichstag – it’s free and fun for kids to run around. However you have to book in advance. I will be writing about it this week so stay tuned! Any other questions about what to do with kids – I’m happy to ask my good friend at Oh_Berlin.com – as I’m sure she has lots of ideas. Just let me know if I can help!

Ugh! Gave me the chills. But it’s something we should all remember so that history does not repeat itself.

You can feel every methodical planning step in constructing and utilising these prisons. It is staggering to think it is so recent in our history.

Really sobering. To think this is part of the history of late 20th century Europe.